The biggest LIHTC project in Utah history shows what’s possible to help solve the housing crisis and empower residents to meet their needs in a well-designed, well-built neighborhood. By Taylor Larsen

Economics isn’t for everybody.

Some in this industry excel in real options analysis to understand risks and returns of capital outlay for a project. Others, like this writer, struggled to understand anything described in Econ 110 lectures. Independent of one’s understanding of economics, everyone in Utah lives through the social sciences’ most trusted law: supply and demand. Namely, the demand to live races onward while the housing supply lags behind.

Utah is the place to live—and the data backs it up. Utah’s net in-migration has been over 20,000 yearly since 2016, according to the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute. Whether incoming residents are seeking the greatest snow on earth or looking to discover linguistic quirks—have a Utahn say “Millcreek” and hear the phonetic difference—there are many reasons to move to the Beehive State.

It’s excellent news for the industry. High housing demand means plenty of opportunities to design and build. The good news continues—the industry built more housing units than new households created in the state from 2019-2022, according to Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute. In 2021, the state set a record, delivering 40,144 new housing units and nearly cutting the reported housing shortage in half.

The bad news? It hasn’t been enough. According to that same data, Utah still needs to build an estimated 37,000 more units, or enough homes to support a city comparable in population to Provo or St. George, to meet 2025 demand.

Answering the Crisis Call

The bad news is glum, but the good news is that developers are helping to solve Utah’s housing challenge, creating expertly crafted homes in job centers like Salt Lake City. Key among these developments is the recently completed The Village at North Station, the largest low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) property in Utah history: a spectacular 827 units.

According to Michael Batt, Managing Principal with developer Gardner Batt, the project helps to meet an urgent need for housing, specifically affordable housing.

“There is definitely a demand for affordable options as we’ve seen significant housing cost increases over the last five-plus years,” Batt said.

Remember the single-issue Rent is Too Damn High Party? What it lacked in political power, it revealed a commonly held belief regarding residential tenancy—the rent is too damn high, especially in Utah. According to the 2022 Economic Census, over 47% of renters spent over 30% of their income on housing.

The Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute showed that Salt Lake County alone lacks the breadth of options to be affordable—190,000 units short, to be exact—for those on fixed incomes, single-parents and one-income households, and those just entering the workforce.

According to Batt, one great tool to meet demand and lessen the rent burden for tenants is “the utilization of the tax credits and bonds” in development across the state, where LIHTC is the most recognized example. According to the Utah Housing Corporation, the independent state agency that administers Utah’s LIHTC program, tax credit awardees receive a dollar-for-dollar reduction on their tax liability in exchange for making an equity investment into affordable rental housing with below-market rents.

Who says the government and business can’t coexist?

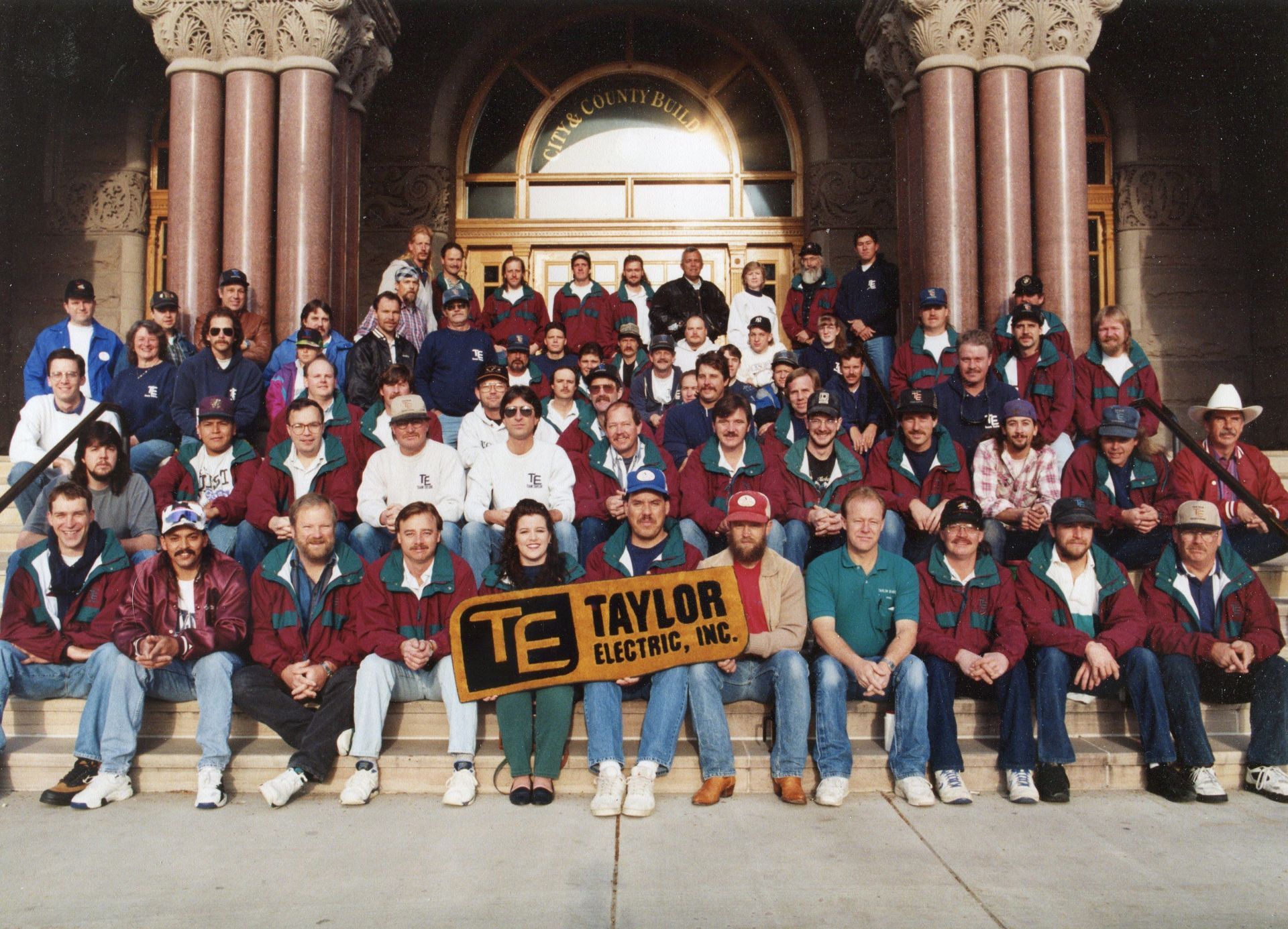

The Village at North Station included 360-degree architecture across each of the eight buildings to give the 14-acre project a welcoming neighborhood feel.

Right-Siting

But make no mistake—this work isn’t happening pro bono. Developing, designing, and building affordable housing is a profitable business. Getting projects like The Village at North Station off the ground comes from the willingness of owners and their A/E/C teams to navigate LIHTC particulars from groundbreaking to ribbon-cutting.

For Batt and his team, it starts with the right site. “We are regularly looking for good sites that are near public transit, work centers, and other amenity bases,” he said.

Call it manifesting, call it “Look and ye shall find” mentality, but Gardner Batt discovered their site—2000 West and North Temple in Salt Lake City.

“This project is right at the last TRAX station before the [Salt Lake City] airport, which made it a great location of both the downtown workforce market as well as the North West Quadrant workforce market,” said Batt. “There aren’t many locations surrounding the downtown area where you can find a 14+ acre site to provide one of the most needed resources in our market—affordable and sustainable housing.”

Mike Ackley, Project Manager for designers Architecture Belgique, wouldn’t give away their trade secrets as affordable housing and transit-oriented architects. “It’s just what we do,” he said with a smile. “It’s our bread and butter.”

As a part of Salt Lake City’s Transit Station Area (TSA) districts by being so close to the 1940 W North Temple light rail station, Ackley said meeting the site’s requirements in design sped the project past a three- to six-month waiting period and straight to administrative review without public hearing. Saving precious time and money requires less of a sacrifice on the architectural side and more of a reprioritization of their values as architects. For something as essential and in demand, time is of the essence. As Ackley put it, “We design for something that is going to get built.”

Toward Something Special

The speed to construction matched a higher design standard required of The Village at North Station due to the site’s TSA designation. The 360-degree architecture conveyed in the masonry, fiber cement panels, and stucco made every side of each building picture-worthy.

“The exposed rivets and fasteners are an intentional design,” said Ackley, describing the work done on the exterior’s white fiber cement panels. The intentionality achieved a high-end uniformity across the entirety of The Village at North Station.

Interiors received the same special touch and prioritized open and inviting design across private and public spaces. Units come with ceiling-mounted fan coils in the bathroom or hallway to keep units comfortable and roomier, while the water heater sits in a room accessible to the maintenance team without ever having to enter the residence.

“The sheer size of the project was challenging to lay out and ensure adequate parking and walkability for the residents,” said Ackley, “but because of the team’s willingness to adapt and innovate, we were able to overcome and create an efficient and sustainable plan.”

One key to connecting the property is the over 300-foot-long cast-in-place concrete midblock walkway. Some walkway slabs received stamping for an extra design flair on the flatwork that traverses the project. This marquee path and the many sidewalks on the 14-acre site deliver a connected, neighborhood feel across the eight buildings and the bevy of amenities.

Beyond the two leasing offices, a conference room is available with private offices for those accustomed to the business casual, while the game room, gym, and pickleball courts cater to residents looking to unwind. On the project’s north side, dog washes, storage lockers, and hanging bike racks sit inside the final amenity building. The splash pad provides another amenity that gave the project team another reason to make this project succeed—resident joy. As the project team prepared to turn over the splash pad for use, residents came out to check in on a future favorite.

“We had all these kids running over here—it was awesome,” said Ackley.

Amenities across the project include a sizeable gym and two clubhouses, for residents of the 827 units to enjoy

Risks Rewarded

Much like how raising children takes a village (pun intended), that same collective spirit was required to construct the largest LIHTC project in Utah history. Ackley and the Architecture Belgique team started designing in 2019, which consisted of seven buildings across a smaller project area before the pandemic changed everything.

“Base plans went out the window,” he said. Not just blueprints but overall scope and general building environment, too. As construction began in late 2022, sourcing concerns required a rethink of many of the originally chosen materials.

Challenges didn’t top out there as prices went up and down like a rogue scissor lift. Idaho-based general contractor Headwaters Construction decided to purchase as much of certain building materials as possible to keep volatility to a minimum and flex their risk management muscle. The general contractor brought in over three dozen 40-foot-long CONEX boxes and 16 storage units rented out adjacent to the site to store building materials.

Because the cost of lumber was trending downward, Headwaters made purchases of the framing materials floor by floor. Put another way, “We gambled a little and just ordered what we needed at the time,” said Bruce Keen, Headwaters’ Sr. Project Superintendent.

The risk paid off.

“I don’t think the project would have been successful without it,” said Keen. “I think a lot of other contractors would just say, ‘Hey, that’s not how this works.’ But we wanted to do whatever we could to make it successful.”

Keen explained that getting materials to the job site was only half the battle, especially as they sought to get into flow. “You’re contending with material for space and the labor required to move it.” As a former subcontractor, Keen recognized that communicative and organized general contractors keep trade partners operating at peak efficiency. With the Village at North Station, peak efficiency meant turning over a building every month.

“If the subcontractor is successful, we’re successful. I want them on that job as little as possible and making the most money possible. We owe it to them to make it as easy as possible for them and earn that buy-in,” he said, mentioning how a quality array of trade partners bought into this pre-purchasing idea and logistics plan that brought flow and success.

However, plans changed as Gardner Batt acquired the third and final property, a former bank branch that faced North Temple, to round out the development. Much like the original designs for the project, drawings changed for what is now Building H—the final part of the project. Instead of a podium with an internal parking garage in the final building, it would be steel framed and add in over 8,500 SF of commercial space on the ground floor to make the project into a future mixed-use powerhouse.

Headwaters was a solutions-oriented GC, so much so that they added Building H into their construction scope and completed it a month ahead of schedule, allowing the entire project to be lease-ready around Thanksgiving 2024.

Leased and Ready

Today, eight buildings across 14 acres of space deliver affordability to the over 2000 individuals and families living in the Village at North Station. Batt recognized that his firm and others won’t solve the housing affordability issues alone. “We hope to contribute to the overall demand for affordable housing options by utilizing our expertise in development to build quality affordable projects,” he said.

Demand is high, much like the demand for owners like Gardner Batt, designers like Architecture Belgique, and builders like Headwaters.

“Even if we’re not on the leasing side, we enjoy these projects,” said Brian Baker, Business Development Manager for Headwaters. “We share similar values with the people that make these projects a priority.”

Solving Utah’s housing project won’t happen all at once. In the meantime, more projects like the Village at North Station and its dedicated project team are most welcome in creating a healthier housing market for Utahns to enjoy.

The Village at North Station

Location: 1925 W North Temple Street, Salt Lake City, UT 84116

Developer: Gardner Batt

Architect: Architecture Belgique

Mechanical & Plumbing: Royal Engineering

Electrical: Royal Engineering

Civil: Ensign Engineering

Structural Engineer: Canyons Structural Consulting

Landscape: STB Design

Interior Designer: KjDESIGNS

General Contractor: Headwaters Construction