For half a century Gerber Construction has forged a reputation of getting the job done—while taking on some of the most challenging heavy-civil construction projects one could imagine. By: Brad Fullmer

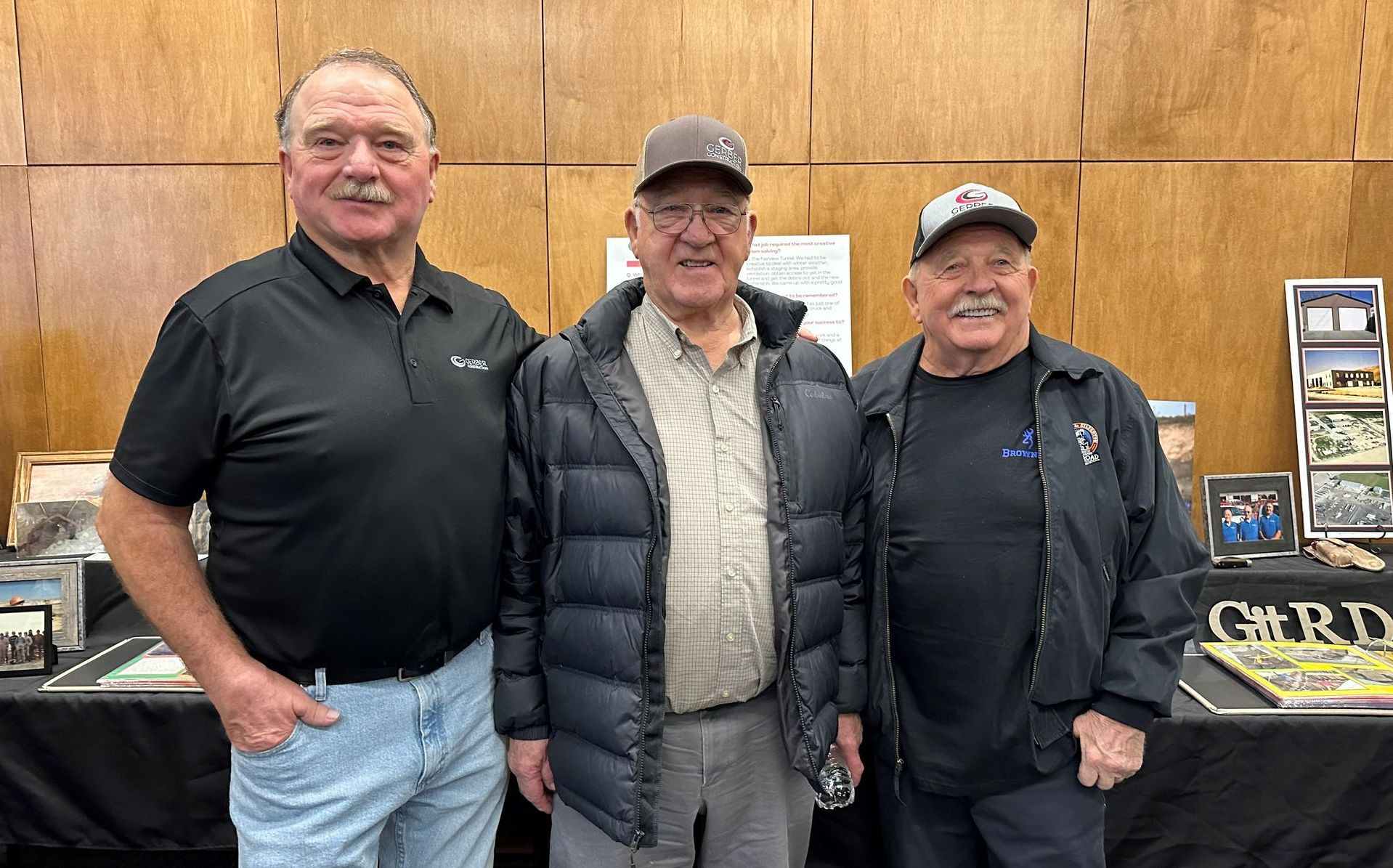

Founded by brothers (left to right: Scott Gerber, Max Gerber, and Preston Gerber) in 1974, Gerber Construction has grown from doing residential work to taking on some of the toughest heavy civil projects in Utah.

Firmly into its third generation of leadership, Lehi-based Gerber Construction has long hung its hat as a heavy/civil contractor on a reputation of taking on some of the dirtiest, nastiest, most challenging construction projects one could imagine.

"One of our niches is we excel at some of the most difficult projects that other people just don't want to be involved with," said Jason Woffinden, President of Gerber Construction since 2019 and a nephew of the founders. "Projects that are challenging, dirty, you have to get in and work hard. That's where Gerber excels."

As the company celebrates its 50th Anniversary this year, Woffinden and current employees have been taking time to look back at the roots of the company, and the Gerber family members that founded and ran it for decades before turning it over the next generation.

"The founders got it to a really great place and we're trying to take it to the next level," said Woffinden.

Father's Can-Do Attitude Set the Tone

Gerber Construction was founded in 1974 by Preston Gerber, who brought along brothers Max, and then Scott, creating a formidable trio whose various skill sets and personalities worked well together.

The Gerber family, headed by parents Clinton and Ruby Gerber, was raised in Wellington in hardscrabble Carbon County. Clinton worked a variety of jobs to make ends meet and feed his family of nine children, including working in the mines, ranching, farming, and construction. The family moved to Lehi in the late 1950s, in part because he didn't want any of six sons (or three daughters) working in the coal mines.

"In Carbon County, if you had a problem you couldn't figure out, you'd call Clinton; he'll figure it out," recalled Preston, who turned 82 in August, about his father's work ethic and can-do attitude. "Us kids are a lot that same way."

Preston spent 15 years working in construction, with time at heavy/highway contractors, general builders, and a supply company, before striking out and founding Gerber Construction after an encounter with a boss who treated him poorly in front of a client. Initially, pickings were slim, but they landed enough work to keep going.

"Back in the mid-70s there wasn't a lot of work, we did whatever I could find," said Preston, "Reed Workman gave me jobs, and I learned the long process of being more efficient than the next guy. We did hard jobs, ones that maybe other people didn't want to do, or couldn't do—that was a big reason for a lot of our success. If we had a job, we made sure to finish it on time or before. If you leave an unsatisfied customer, you'll lose them. Make sure things are done according to the agreement, or better."

Preston was the ringleader who landed jobs, Max ran the books/administration tasks, Scott made sure projects got done right and on time. It was a near ideal relationship. They worked long, hard hours, burning the candle at both ends to keep the fledgling business alive.

"Preston was the visionary; Max was more business-minded, the finance guy; Scott was the lead superintendent, and he was assigned to all the tough projects," said Woffinden. "In the early days they were all out together building the projects, and then at night doing whatever else needed to be done behind the scenes, whether it was Scott fixing a truck in the garage or Preston going out of town to bid another project."

The first five years the firm did a lot of residential concrete work, but by 1979 they had moved out of single-family housing and into the public sector, bidding on more complex public works projects. Scott bought in as a full-time partner in 1977.

"The best move we made was getting out of residential and doing public works projects," said Max, 81. "Public works funding is always there. Preston was good at sizing up a job and knowing where to start. He wasn't afraid to bid a tough job."

Sometimes, that meant working consecutive shifts on different projects. Max recalled pouring concrete on one job and having Preston show up at 11:00 am announcing "cancel the rest of your pours; we have a warehouse floor to pour right now" on a second job.

"We got to the warehouse by noon and didn't get off it until (10:00 pm)," Max laughed. "Preston sometimes was a little more aggressive than he should have been, but that develops an attitude that you can do anything."

As the company grew, Preston eased his way out of field work so he could pursue business development work and land jobs, Max kept the office humming, and Scott kept the workforce in line and on point.

"We all knew our parts; we have complete faith in each other," said Scott, 68, who retired December 31 last year after nearly 50 full years. "Preston had a nose for money jobs. A money job is the job with the most potential for disaster. The harder it is to do, the bigger the reward. He'd go out of his way to find them, and he'd stick me on them. It took some time to adjust to the technical jobs and also working in the elements. We worked year-round—there were no winters off."

The company gradually grew its portfolio and expanded its capabilities to construct water projects, bridges, and other heavy/civil structure work. They were willing to take on projects of all sizes and scopes, not just the massive, behemoth jobs.

"We figured out that you can make more [profit] off three $5 million jobs than one $20 million job," said Preston. "It suited us to get in, get the job done, and get out. If you have a bad job, you've got a two-year hurt."

He praised his brothers for their ability to do their jobs at a consistently high level, which also led to greater profitability.

"We would not have been as successful if Max hadn't managed the money," said Preston. "I can make the money, but I spend the money. Max accounts for everything and he's really good at it."

He added that Scott "can take complicated things and make them simple" and can "find solutions that would take weeks, and have it solved overnight."

Building Up Employees Key to a Stable Company

The Gerbers took great satisfaction in the people they hired, trained, and developed over the years. They were conscious about helping steer people along, realizing that the type of construction they did required a tougher-than-normal work mentality. Often times, workers had to be coached up, encouraged, and genuinely praised for their efforts.

"If you give them a reason to get up in the morning, you give them a job with dignity, you'll get more years out of that person and he can support his family and make money, it's not just a gift to him," said Preston. "Scott was really good about bringing people up. Scott will take less qualified people and fewer of them and make the company more money on a job."

"I always had the youngest crew," said Scott. "I was the end of the line—you either sink or swim on my jobs. I've taken a lot of young men who had problems and found out who they were. When it's all said and done, it's what you taught other people; I wished I'd known that sooner. But I still have guys calling me for advice—that always makes you feel like you accomplished something."

Woffinden proved his worth in the field starting in high school during summer, then full-time after a two-year church mission to Scotland from 1988-1990. Woffinden long revered the Gerber work ethic and penchant for hard jobs, and eagerly accepted working difficult projects as well.

One such job occurred in the mid-90s at a soda ash mine outside Little America, Wyoming, he recalled. While the cozy confines of the famed Little America Hotel—excellent food and the hotel's signature gold or blue shag carpeted rooms—were a welcome respite to workers after a tough day on the job, being tasked with adding a 40-ft-long concrete shaft with a flume at the end to an existing 200-ft.-plus mineshaft offered untold challenges, compounded by brutally-cold weather.

"It was 25-below zero in January and they were drilling the shaft as we're forming [concrete]," Woffinden said. "When they punched through, the temperature of the air coming out of the ground was much warmer—you could see this column of mist from miles away. We had to wear rain gear in there, it was so wet. They're mining [soda ash], a white powder that gets in the mist...you'd go outside and it would just freeze on you. It was a tough, nasty job."

In addition to Woffinden, two other family members have more than 60 combined years at the company: Preston's son, Brandon Gerber is a General Superintendent with 36 years of experience; Max's son, Lance Gerber, is a Superintendent with 28 years at Gerber. Preston said he's proud to have family members in key roles. He's long been impressed with Jason's leadership and passion to grow the company and continue the Gerber legacy.

"He's always had a fire in him," said Preston about Woffinden. "It takes a good combination of people to have a successful company. If you're cutthroat about it, it's the wrong way of doing things. If one of your guys is in trouble, you step up and take care of it, make sure he has what he needs. I'm proud of Brandon and Max is proud of Lance—they're doing responsible work. Gerber Construction has been a support for a lot of people and families and we're proud of that."

Consciously Taking the Firm to the Next Level

A fourth Gerber brother, Allen, also spent 20-plus years at the firm, including a dozen years as top executive, before Woffinden took over in 2018. He said he realized several years before being named President that "if we're going to continue to progress [the firm] we have to develop our structure, our processes, and our systems better, and get the right people in the right positions. We have to be more intentional on the markets we're going to work in, and we need to be more goal oriented."

So difficult changes were made, processes are continuously tweaked and improved upon, and new technologies/techniques are implemented regularly—all in the name of building a stronger company. Woffinden is highly motivated to keep the ship moving forward another 50 years. Giving others an opportunity to buy into the firm as shareholders is also critical to future growth and success, he said.

"We're more united as an ownership group about the direction we're going," said Woffinden. "We have more trust in department leaders, we rely on executives to make good decisions so we can expand the ability of more people. I only have so much capacity, so the biggest challenge is finding qualified personnel to do the job. That has been overwhelmingly difficult."

In the last five years, Gerber has grown from 130 to 180 employees, an average of 10 people annually—no small feat with today's labor pool challenges. In June, the firm finished a renovation/expansion of its 20-year-old headquarters in Lehi, adding a more open layout to the office with modern design elements and optimal functionality—including more offices, conference rooms, training rooms, and a sizeable breakroom.

To maintain a strong employee base, Woffinden said leaders are expected to mentor and help retain personnel.

"Our retention piece is equally shared among executives, supers, and foremen," he said. It's about building good relationships." The firm shuts down twice a year for conferences in the summer and winter, and they have a 14-week, in-house training program for crew leaders.

"Our mission statement is to be a company of choice, while still maintaining our core values and principles," he said.

Woffinden is proud to lead a firm with such a strong reputation and grateful for what he learned over the years from the Gerber brothers.

"The founders, the way they were raised, I idolize that," he said of his uncles. "They were forced to do things that were tremendously difficult. They had to make a go of things on their own. When Preston started the business, he had the mentality of 'you don't give up, you don't quit'."

Woffinden said many jobs required 90-hour weeks at times, depending on a project's schedule and how much more needed to be done.

"In the early years, whatever it took is whatever it took to get a job done," he said. "You had to be part of the project, buy into it [...] work nights and weekends. We went out of town a lot. Our motto at one time was 'We travel for hard projects'."

"I'm definitely motivated to grow the company and provide opportunities for our employees," he added. "The market is there—somebody is going to do it, why not us? We have the teams to do it. That motivates me and excites me. I'm all about constant improvement."

Notable Gerber Projects

Project Name Location Year Cost

Nutrient Removal (BNR Basins) Salt Lake City Active $123 M

Silver Creek WRF Expansion Park City 2019 $43 M

SR-270/900 South Connector Salt Lake City 2018 $4 M

Green River Tusher Project Green River 2016 $6 M

Echo Dam Spillway Weber Canyon 2014 $9 M

Murdock Canal Trail & Expansion Utah County 2014 $12 M

CWP North Shore Reservoir Saratoga Springs 2014 $16 M

Central Utah Upper Diamond Fork Spanish Fork 2004 $4.9 M

Olmstead Flowline Reach A Provo Canyon 2004 $2.2 M

I-80 Bridge Rehab Parley's to I-15 Salt Lake City 2001 $4 M