Architects and designers share insights and thoughts on how design and architecture can better lead toward a healthier, sustainable built environment. By Taylor Larsen

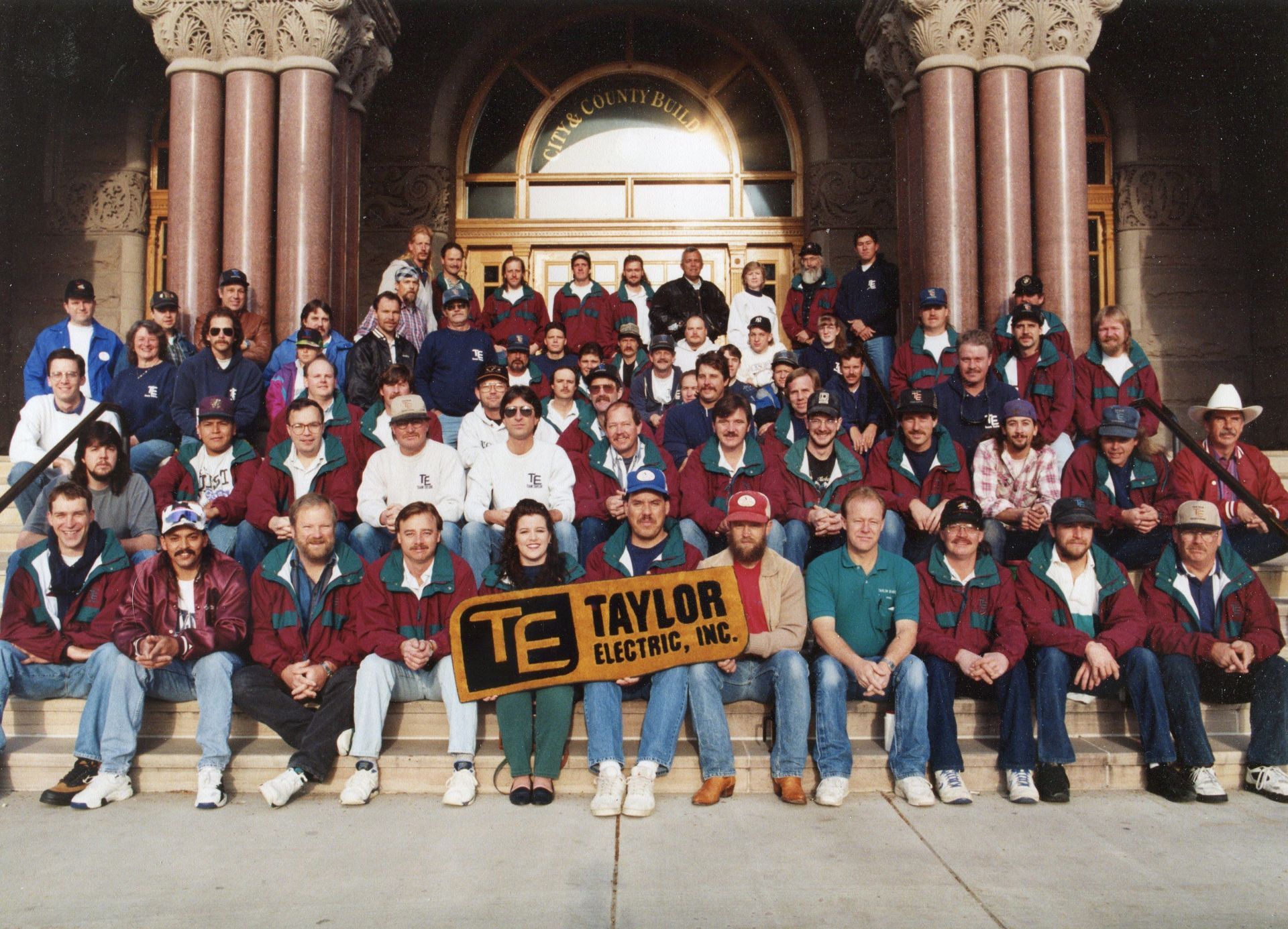

Polk Elementary (Ogden) is and FFKR project (2022 Most Outstanding Project--K-12) that renovated and added to the original, 1926 school with biophilic elements like natural maple wood slats.

Active Benefits from Passive Design

For Kenner Kingston, Principal of Salt Lake-based architects and consultants Place Collaborative, a winning message for sustainability is one that creates a built environment that is part of a healthy ecosystem—one that pays for itself over time and contributes to a higher quality of life for users, visitors, and the nearby community.

Less complication and interventions; more of a look to nature to inform design.

“When buildings and people are in symbiosis [and] are part of an ecosystem, occupants are empowered,” he said. This symbiosis starts with passive design, a strategy that works within the existing environment to maximize natural efficiency.

Step one in passive design is orienting the building correctly on-site to maximize daylight. Kingston said all of this starts with architects.

Much like Earth, passive design revolves around the sun to ensure the right amount of daylight warms up the space—literally and figuratively—in the winter and stays comfortable during the summer. It’s something that nearly everyone can agree since “it’s not a mysterious technology, it’s daylight.”

Next, the building must maximize its building envelope with best-in-class walls, doors, and glazing. Kingston credits work done in building codes to make building envelopes much more efficient now from when he started practicing architecture in 1996.

Kingston emphasized that today’s built environment needs a return to the basics of passive design, where buildings require a bit of work from users to function at peak efficiency and comfort while still being firmly rooted in a connection to nature.

“A normal building has a lot of automation for occupants to be comfortable,” he said. “Automated systems make us powerless. […] Passive buildings do a lot less, and occupants are expected to do more.”

He pointed to Architectural Nexus’ award-winning Daybreak Library, where he and fellow Place Collaborative Principal Holli Adams asked via design for the building stewards to actively participate in the library’s success.

Their “demands” from the library team weren’t radical.

“Turn off the lights, open the windows, go to the courtyard,” he said. “Participate in this ecosystem.”

Librarians there report feeling pride in helping it function at peak efficiency. Whether that was meeting the demands above or removing the “greatest snow on earth” from the building’s solatubes to bring light inside, they become invested in the building’s success by understanding how the building works.

“[Passive design] is more engaging,” he said. “When someone cares about a thing, they tend to take care of that thing.”

The veteran architect is under no illusion that every building must be net-zero or LEED Platinum. But starting the question: “What would nature do?” will lead the entire industry to answers readily available.

“There's no mystery,” he said, “we just need to try.”

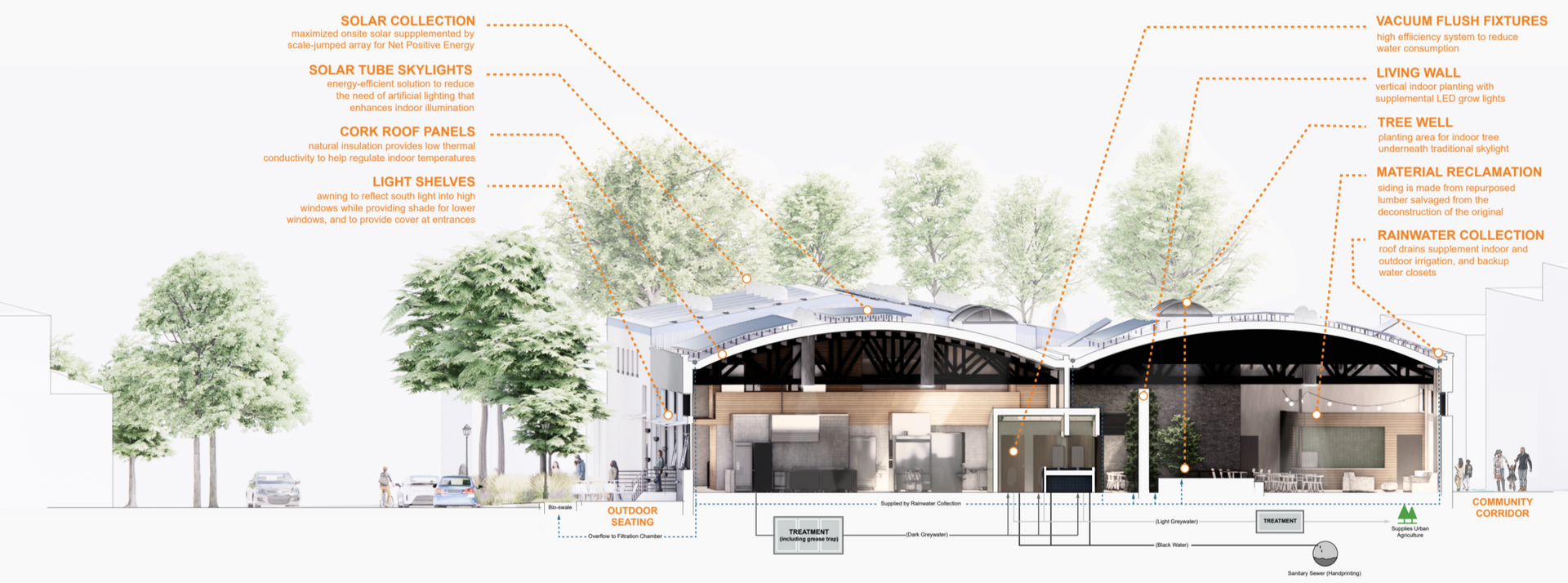

The McKay Education Building currently under renovation at Weber State University will be complete this summer. Designed by GSBS, it is a great example of sustainable design with creative daylighting as well as integrated and high-efficiency HVAC, lighting, and photovoltaic systems. (image courtesy GSBS Architects)

Health & Wellness

For Caitlin Gilman, the term “sustainability” is too broad. To be effective, she said, design teams need to hone in on their goals to create a healthier built environment.

“So much is placed under that ‘sustainability’ umbrella that it’s difficult to understand what someone is trying to achieve,” said Gilman, a Sr. Associate at Salt Lake-based FFKR Architects. “With that said, it’s a term clients are familiar with and a good starting point for what clients want to achieve.”

Gilman has found that clients like the checklists that certifications like LEED, Living Building Challenge, and WELL present as a baseline or goal but are less interested in plaques and certifications. Clients are more prepared than ever as they begin project talks with a sustainability framework already in mind.

“We’re seeing less of the architect bringing sustainability to the table and a move towards clients and owners coming prepared with goals in mind,” she said. “Sometimes where they’ve already hired a third-party energy consultant.”

As the sustainability conversation has shifted from solely focusing on energy or water use to an approach concerned with quality of life, Gilman reported that efforts are trending in the right direction.

“There’s an increasing awareness of what physical impacts harmful products have on the body,” she said. Whether that is moving away from products containing VOCs or embracing natural materials in building materials, “Curiosity about what makes up our building products and selecting red-list free materials is becoming more prominent.”

Economics may be in the driver's seat, but those ideals aren’t mutually exclusive. She detailed how mass timber’s speed of construction became an “open door to more sustainability talks” for FFKR and their client. Ultimately, the mass timber design walked through the door to approval.

First costs and operational costs still hold most of the power in these discussions. But Gilman said the indirect costs and benefits of a healthier built environment are gaining traction.

“Recognizing the connection our built environment has to psychological wellbeing” is growing in importance, she said. “We’ve seen an increased interest in biophilia and connection to the outdoors.”

Improving test scores in educational settings, better working and living environments, and better health outcomes for tenants, visitors, and society as a whole are all benefits that come into play with these talks.

But, Gilman cautioned, all of this talk is for naught if our built environment is torn down and replaced every few decades.

“Enduring materials and reuse is a component of sustainability that often gets overlooked in favor of the newest technology or trend to add to a project,” she said. “It doesn’t matter what product you put in there if it is not built to last.”

She’s optimistic about the future, particularly as the conversation moves toward wellness.

“As architects, we have a responsibility to our buildings’ occupants,” she said, “and the growing recognition of how the built environment influences physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing represents a crucial evolution in our approach.”

Human Oriented; Nature-Focused

Shalae Larsen said landscape architecture is an integral part of sustainability in the built environment, especially for the opportunity to connect to nature.

Larsen, Co-founder and Principal of Ogden-based Io LandArch, led the afternoon plenary session at the Intermountain Sustainability Summit. She and fellow speakers noted the good work being done across Utah to create landscapes and green spaces where residents want to be.

Larsen noted in this interview that the desirability of those green spaces in the form of programming and amenities is important for visitors but not the critical component to success.

“[Visitors] want the areas to be,” Larsen emphasized.

As she put it, effective landscape architecture tells a story. It doesn’t need a “moral of the story” in plaque form. The best landscape architecture projects imbue a sense of meaning.

For parks, that means spaces where a wide variety of activities occur. That can mean open lawn areas can accommodate games, picnics, or kite flying. “Trail systems are great for fitness or walking with friends, family, and pets,” she said. “Different trails can offer a different range of experiences.” Places for people to sit and gather, meditate and think, or simply people-watch are always important in terms of activating a space.

“It’s not just natural connections,” said Larsen. “This digital world is isolating. People are seeking out stories and connections.”

Advancements in the built environment, she said, are technology-heavy, which has been great for efficiency in energy use and water conservation. “But why are we embracing technology? It’s for us,” she said. “That’s what’s compelling. And that’s the starting point we need to move back to.”

The A/E/C industry must get back to the human focus.

“The move toward therapeutic landscapes—outdoor spaces with elements that promote mental and physical well-being,” she said, “this is what creates lasting projects that people will cherish.”

“This approach not only enhances the aesthetics of a space but also contributes to the overall health and productivity of its users,” she said. “It reflects a deeper understanding of the role environment plays in human well-being.”

She said landscape architecture is trending in the right direction on these fronts, moving away from “shrubbing up” sites just to meet minimum landscape requirements. Best practices are also moving away from big areas with rocks-capes to try to minimize maintenance while unintentionally creating heat-island and stormwater management issues.

Instead, more organic, engaging, and people-focused landscapes are coming aboard. According to Larsen, some of the most promising changes come from integrating native and xeric (drought-tolerant) plantings and creating bioswales or rain gardens to manage stormwater naturally.

Developers and business owners are joining in as they look to build an identity rooted in ecological causes or create the ambiance for employees to thrive.

Larsen pointed to work performed on a nondescript commercial building on Wall Avenue in Ogden. Io LandArch worked with the developer to expand the interior courtyard surrounding a fully grown beech tree, creating a space that helped attract the new building occupant, Hyperthreads. The custom outdoor and athletic apparel company is a perfect fit for the space and the nature rooted within.

“Hopefully, it's more than a trend,” Larsen said of these efforts from businesses to shovel resources to amazing outdoor gardens and dense interior plantings. “We need more places for people to interact with nature in a more meaningful way than just looking at greenery.”

Developments focused on people and connected by nature are the way toward a sustainable and ecologically impactful built environment.

“At the end of the day, our job is to build sustainable buildings for human beings,” she said. “Emotions and experiences are going to be what drives them to support future sustainability and future environmental policy.”