Concrete Future

Jacobsen Construction began running out of room in their corporate headquarters in West Valley City over five years ago. People were in triple-wide trailers in the parking lot, while others, President and CEO Gary Ellis said, were in the building, one colloquially known as “the maze” because of its labyrinthine offices and areas.

It was at that point that Ellis and former CEO Doug Welling said, “It’s time.”

The time, specifically, to move into a space befitting one of the biggest contractors in Utah. “We want to be in the talk as the best contractor around, and we felt like [a new headquarters] would be important for our future,” said Ellis. “Where we could plant a flag here for the next hundred years.”

Settling on Location and Design

With buildings and development expanding westward, the Jacobsen building committee felt that the opportunity to be a part of that growth was too good to pass up. Now, their headquarters resides in Salt Lake City just west of the airport in the International Center.

Inspiration for the Jacobsen Corporate Office came from the Life Sciences Building at Utah State University, another Jacobsen/VCBO Architecture collaboration. Burke mentioned the metal paneling, extensive glazing, and GFRC on the exterior were choices that came about from UC&D’s 2019 Most Outstanding Higher Education Project.

Payne was complimentary of Burke and the team’s effort to bring design choices to life—specifically regarding the constructibility of the GFRC façade.

“They found this way to look at the material and make it other-worldly,” he said, pointing out the process of treating the GFRC like brick—bringing about the lovely cream colors that blend so well with the dark metal panelling and concrete touches on the exterior.

The themes present in the building center around light and collaboration. The three levels, according to Payne, “was a better way to communicate [than single-story]. You can get everywhere [in the building] very quickly. The whole idea of the central stair […] was a key to collaboration.”

Efficiency and economy in both cost of the building and in movement were a great starting point to meet the company’s goals for a collaborative space.

Meeting the Scope

In internal documents, the company looked to construct a building that effectively and invitingly portrays the Jacobson experience and the Jacobson culture to both employees and visitors.

That goal is visible immediately upon entry, with the company’s expansive lobby projecting not just depth of expertise in the concrete forms throughout the lobby. Wooden risers and steel beams support the staircase and provide more visual nods to the contractors expertise as visitors and employees climb to the second and third floors.

“Everything is compartmentalized,” Burke said. He and the other workers who shift between field and office can chat with their fellow project managers and project executives. Accounting, HR, IT, and estimating (with their unique, “War Room” table and less unique but still combative ping-pong table) have their own dedicated spaces that accommodate both present and future needs.

The space currently holds the 120 employees who regularly pop into the office, with Ellis mentioning that the space has plenty of room for growth. Training rooms downstairs can fit up to 200 people—craft workers for a safety training or the whole office for a company-wide meeting—and it isn’t just for Jacobsen employees, either.

“We want clients to come and use our space,” said Ellis. Whether that is architects coming in for an off-site meeting, engineers looking to strategize for the future, or even groups like ULI, who have used the space already, Ellis said, “We want the industry to come in.”

Showstopper

What they will see is a testament to the firm’s quality, especially in concrete. Burke suggested putting reveals in the forms to help keep the visual consistency of the concrete. It’s just one part of the “showpiece” of Jacobsen’s self-performed concrete work.

“Jacobsen made this their headquarters for life,” said Payne as he spoke of the bones of the building. Eighteen inches was their prescribed thickness for the concrete walls, according to those interviewed, but that would only be decided after Burke and others watched all their work potentially dashed in the 2020 earthquake.

“Watching those walls flap around in the air was unnerving at best,” said Burke with a grimacing smile. “We had poured and stripped our first lift of [walls] when the earthquake hit. Watching them sway four to six inches” had him and others fearful that all that work would be for naught.

But the structure stood firm, and 15-foot lift after 15-foot lift after 15-foot lift got tied into the structure to bring it up to its three-story height: 2,550 cubic yards of concrete. A mark of pride for Burke is the quantity of 90-degree angles on the various concrete forms, but the showpiece of all of that concrete is the chosen angle for the exterior that faces the lake.

It’s 30-degrees, the corner rising from ground level up three stories—an impressive feat. “It’s a sharp corner,” said Burke, marveling at the work. “It would split something up like a melon.”

The quality in concrete construction was a high point for Burke, but his favorite feature is the ground-level boardroom. While concrete is also prominent there, the views through the exterior glazing, dimmable interior glazing, the wooden panelling on the ceiling, and the art present there make it a comfortable space to make the big decisions.

Interior Charm

“There are objects, and then there is atmosphere,” said Payne of that main boardroom’s massive table. It’s a favorite part of the building for him. Payne explained that he drew inspiration from a Viking ship, an ode to Jacobsen’s Danish history. With the scenic lake nearby, “[the table] was meant to be this ship that is going toward the lake—like it’s seaworthy.” The atmosphere that brings together the space is simple grandeur.

The interior maintains the company’s goal of vibrancy. No boring board rooms or stuffy offices here, but 18 collaboration spaces join the various individual offices that nestle on the exterior walls. Each office has enough glazing to make that visual theme pop.

Sloped ceilings near the glazing shower the entire office area in sunlight. Jacobsen and VCBO also incorporated “neighborhood” concepts outside of the offices and work areas for the informal meetings, the all-important “meeting after.” These spaces have construction’s version of coffee table books, Walker’s Building Estimator’s Reference Book, but, more importantly, they have the the subtle nods to Jacobsen’s roots as a construction firm.

“It’s almost like a whisper,” said Amy Christensen, Executive Vice President, Corporate Communications & Brand Marketing for Jacobsen. “You want the whisper between the utility and sense of meaning.”

And those whispers are heard throughout the space. Whether via the self-performed concrete, the steel beams that double as bookcases in the neighborhoods, or the wood paneling on the ceilings, the execution perfectly straddles the balance of utility and aesthetics.

Employees, Tenants, Owners

As an employee-owned company, one accountant came up with a type of suggestion board “Wish List” with many different ideas to help the building committee. Some of the suggestions were comical, like the pinball machine, while others were universally praised and incorporated, like “The Grand America” bathroom concept, where stalls and bathrooms would be totally private and no one needed to check out the shoes of the person the next stall over.

But other choices had folks drawing battle lines. Some wanted open office, others felt like their work would deteriorate in noisy conditions. The solution, according to Ellis, was, “Turning to department heads to figure out what works best for them.” And figure it out they did by allowing each to find the perfect balance. “Accounting services are a more social group and wanted the open concept […] [while] virtual design and construction wanted the ability to shut the door.”

With lots of interior glazing to complement the daylighting shining through the 83 windows, transparency, openness, and the vibrancy of a bustling office are on full display.

Speaking of displays, the “J-Hub” helps to blend office and field work on a massive touch-screen near the company’s lovely self-service café. It’s part internal communication tool, part recruiting tool, full unifier of purpose. “We use it for all kinds of things,” said Christensen. She was excited about how that sentiment in the J-Hub reverberated throughout the building.

Artistic Reminders

Other, more traditional art pieces adorn the building, too. Jacobsen Construction chose four individual art installations and two photo galleries to add additional energy to the interior, with help from design and branding professionals at Struck.

Some serve as a rendition of work the Jacobsen does, with two pieces using reclaimed wood from the company warehouse and yard. Others serve as more abstract visions of the company’s mission and connectivity to the greater community.

“We took a hard look at ourself and asked, ‘How do we translate a legacy of 100 years, where we want to go in the future, and have it resonate with employee ownership culture?’” said Christensen.

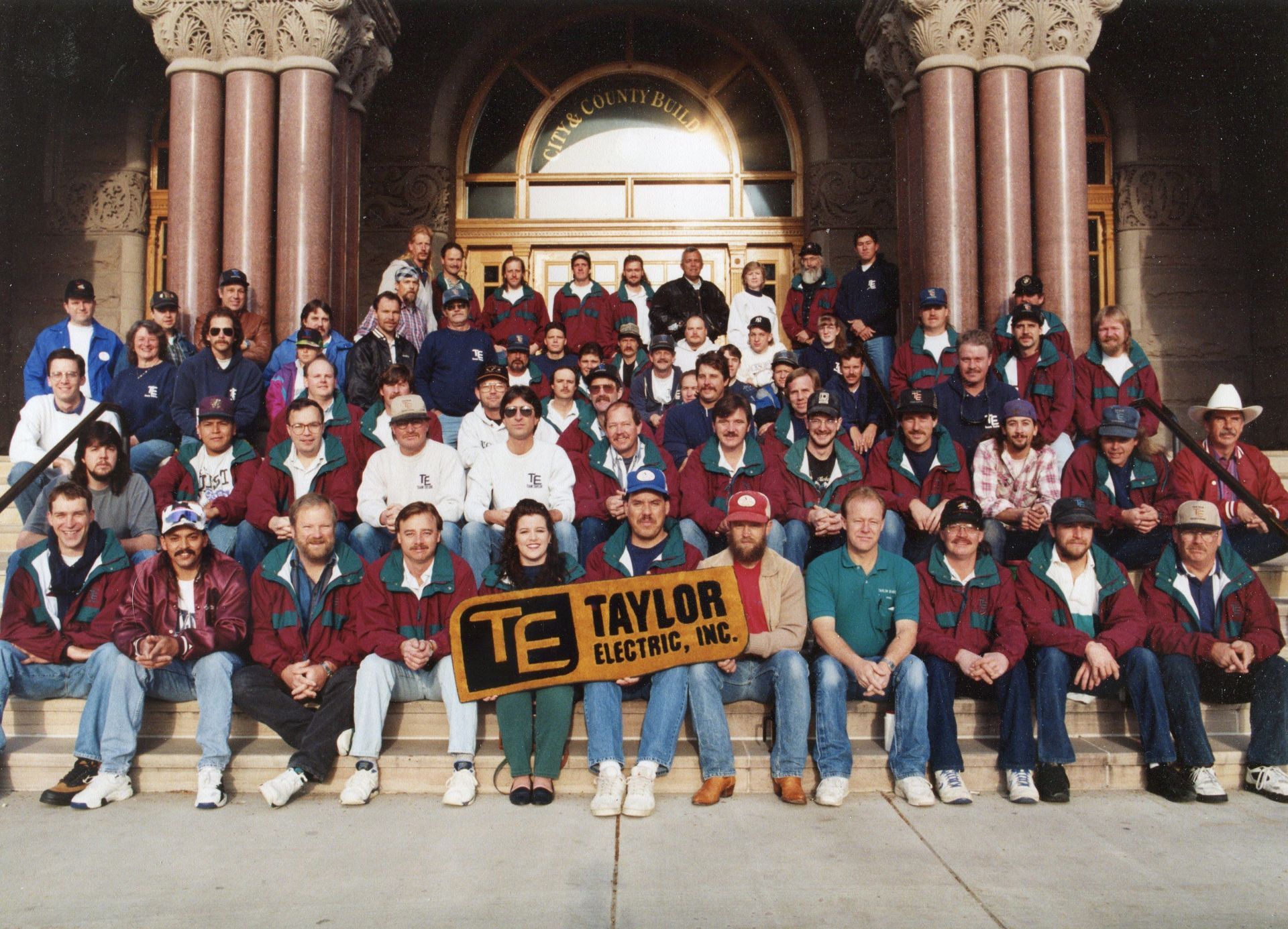

That translation comes in every piece, specifically via the photo galleries. One, “Hard Work” celebrates the many hands that have built the company up for nearly a century—that’s the “how.”

Ellis gestured toward the other, “Built for Life,” during the interview.

“This is ‘why’ we do it,” he said.

The gallery is a reminder of the importance of these buildings for the people who inhabit them: expecting mothers at the hospital, worshipers at a church, students at school, employees at an office. It’s a lesson that wasn’t lost on Burke as he led the building efforts during construction.

“Every building we build has its challenges. As contractors, we walk away and say, ‘Oh, I made it through that one.’” He said. “But being able to enjoy the finished product […] has been my favorite part of this project.”

Does he get a lot of high fives? “Yes,” Burke smiled. “I get a lot of people telling me ‘You did a good job. It’s a beautiful building.’ A lot of people are really happy about it and happy about their new home.”

Legacy and Future

The weight isn’t lost on Payne either, who spoke to the work done by the entire building committee as they moved the project forward.

“Best voicemail I ever got was from Dennis Cigana,” he said of one of his favorite memories of the entire project. “I’ve never heard someone say [what he said] about a building. He told me, ‘You got us everything we wanted out of the building.’ He and [Jacobsen Construction] were such a joy to work with.”

At the ribbon-cutting, Cigana, Chief Development Officer for Jacobsen, stood next to Ted Jacobsen, former owner of the company. Ellis recalled the conversation with Jacobsen saying, “What have you done?” with a wry smile.

The comment may have been in jest, but he heard Cigana say, “Ted, this is what you have done.” He credited Jacobsen for charting the company toward its present course.

So where is Jacobsen Construction now? It’s one of the top general contractors in the state, now with a building that fits the brand of which Christensen spoke so highly. It’s a building that represents the strength and stability of the company.

“We’re not going anywhere,” concluded Ellis. “We’re here to stay and to do great things.”

Jacobsen Construction Company Headquarters

Location: 5181 W Amelia Earhart Dr, Salt Lake City, UT 84116

Square Feet: 58,836 SF

Design Team

Architect: VCBO Architecture

Civil: Meridian Engineering

Electrical: Envision Engineering

Mechanical: Colvin Engineering

Structural: Reaveley Engineers

Geotech: GSH Geotechnical, Inc.

Landscape: ArcSitio Design

Artwork: Struck

Construction Team

General Contractor: Jacobsen Construction

Concrete: Jacobsen Construction/Gene Peterson

Plumbing/HVAC: CCI Mechanical

Electrical: Hunt Electric

GFRC: Allen’s Masonry

Framing/Drywall: Pete King Construction

Painting: Pete King Commercial

Acoustics: K&L Acoustics

Millwork: Boswell Wasatch

Carpet: JCC Flooring Division

Polished Concrete Floor: Stone Touch

Roofing: Utah Tile and Roofing

Glass/Curtain Wall: Steel Encounters

Interior Glazing: Midwest D-Vision Solutions

FF&E: Midwest Commercial Interiors

Waterproofing: Guaranteed Waterproofing

Steel Fabrication/Erection: JT Steel

Site Utilities/Asphalt: Morgan Asphalt

Steve Green is out in McCornick, Utah. Where is that? And what’s near McCornick? “Nothing,” joked Green, the Sr. Vice President for Wheeler Machinery Co. While he may be far from even the smallest of small towns, with Holden and its 492 residents 13 miles away, he’s close to the site of a major development in data center technology. Isolated on the western edge of the Sevier Desert, the Joule Data Center will also be isolated from the grid—by design. Operation Gigawatt Rolls On Green is one of many energy and power professionals hoping to double Utah’s power generation capacity by 2034 as a part of Operation Gigawatt, an initiative launched by Utah Governor Spencer Cox in October 2024. Utah has long been an economic growth leader; Operation Gigawatt aims to make Utah a power player in energy development by increasing transmission capacity, increasing energy production, strengthening policy, and investing in energy innovation. While Governor Cox’s Operation Gigawatt moves forward statewide, out in McCornick, Green said, “We’re doing operation gigawatt and a half off grid.” The Joule Data Center project team will deliver “In-situ power generation”—power not connected to any electrical distribution or transmission system. It starts with Caterpillar G3520K reciprocating generator sets that produce 1.5 gigawatts of electricity. Waste heat and exhaust from the generators then move through an absorption chiller system as part of the overall systems combined cooling, heat, and power (CCHP) solution, providing much of the water required to cool the data center servers. Beyond the electric power to be generated for the Joule project, there will be 1.5 gigawatts of thermal energy and 1.1 gigawatts of available battery storage to meet the data center's peak electricity needs. Added Green, “And we’re not taxing the local utility grid.” Isolated or Community Power? The massive power capabilities delivered there are impressive, but they reveal a troubling trend in how Utah will double its power generation capabilities. Will it be from well-funded companies looking to power data centers and AI technology separate from the grid? Or will Utah fulfill the mission of Operation Gigawatt by creating power solutions accessible to all? According to Troy Thompson, Chief Operations Officer for Big-D Companies, power generation is about more than supplying data centers. “In my mind, how do we build a billion-dollar hospital downtown that needs ten megawatts of power?” he said, referencing Intermountain Health’s future downtown Salt Lake campus, “let alone the data centers, and manufacturers who we are hoping that will come here?” Ten megawatts of power may pale in comparison to what data centers require, but it is one of many projects seeking regulatory approval to move forward. The Utah Inland Port Authority, the Economic Development Corporation of Utah, and others continue to drive projects and jobs into Utah—data centers, too. But Thompson said he has heard from many potential clients who are hesitant to bring their energy-intensive projects to the state without firm guarantees of available power. Operation Gigawatt and state leaders have embraced an "all of the above" approach to energy sources, extending the design lifespans of coal plants, embracing new technologies and power sources, and developing new power-generating capabilities. While the industry is willing, the operating environment needs rewiring to meet state goals. Changing for 21st Century Needs “With as hot as the Utah market is,” began Eric Haslem, “there are too many obstacles for us to overcome.” The market may be ready to ramp up production, said Haslem, Chief Operating Officer for Vernal-based utility and heavy civil contractors BHI, “But the current system can’t handle it. We have this massive web of transmission and distribution infrastructure that was not designed or built for the power demands of the 21st century.” “In 1970, they didn’t know what a smartphone was,” Haslem said, “let alone AI.” Transmission projects have been developed. Rocky Mountain Power/PacifiCorp’s Energy Gateway South transmission line—a 416-mile, high-voltage 500-kilovolt transmission line that runs from Mona to Medicine Bow, Wyoming—certainly helped when it went live in 2024. Still, it's just one project amidst a plethora of needs. Haslem stated that Utah's growth over the last 10 years meant a large majority of the transmission line's capacity was accounted for when it went live. .

And the King shall answer and say unto them, "Verily I say unto you, inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me."—KJV Matthew 25:40 From a social and community impact standpoint, few projects match the value to disabled and special needs individuals as the new Utah State Development Center (USDC) Comprehensive Therapies Building in American Fork. The $36 million, 65,000-SF facility was designed as a "one-stop shop," said Joe Jacoby, President of Salt Lake-based Jacoby Architects, whose team led the project’s design. It consolidates and modernizes myriad services under one roof, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, recreational therapy, speech, language, and hearing resources, and behavioral health resources. In addition, the new building offers full-service medical and dental clinics, an indoor therapy pool, an Autism treatment wing, and workshops for life skills and vocational training—all geared to helping people live independent, authentic lives, while striving to reach their full potential. "This building was very much about accessibility," Jacoby said, "and putting in many different types of resources for these residents—all in one building." Jacoby's firm has significant recent experience in projects that combine education and healthcare for people with special needs. The firm's design of the Sorenson Legacy Foundation Center for Clinical Excellence in Utah State University's College of Education and Human Services earned UC+D's 2016 Most Outstanding K-12 Project. Two years later, the firm earned another UC+D award for the C. Mark Openshaw Education Center for the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, a project similar to this one in that it contains an array of services, including education and therapy for varying levels of sensory, behavioral, physical, and cognitive abilities. "We've been working on different [design] aspects for many years, starting with a deaf preschool, which led to working with the Utah Schools for the Deaf and the Blind," said Jacoby. "With that came many other sub-specialties, like therapy for behavioral issues, cognitive issues, development disabilities, and even speech, language and hearing clinics. It helps people with a variety of disabilities and serves an underserved population of people."

On a fall tour of Utah State University's (USU) Carolyn & Kem Gardner Learning & Leadership Building (Gardner Building), students and faculty are hard at work on a late Tuesday afternoon. Getting here, where USU's business school students could thrive, was a long time coming. The University commissioned the Gardner Building to meet a new mission for the school outside the traditional knowledge acquisition and transfer for which USU has excelled since its founding in 1888: Giving students a differentiated experience they cannot get anywhere else. Purpose Revealed Frank Caliendo, Senior Associate Dean of the Huntsman School of Business, said that the new building is the third and final piece of the business complex, "a realization of the longtime vision of Dean Douglas Anderson, the driving force behind the school's transformation, to meet the needs of students for generations to come." Caliendo, a longtime Aggie (USU BS, '98; PhD, '03), said that, even after the opening of the George S. Eccles Business Building and its faculty offices and classrooms in 1970, growth in business courses eventually outpaced the school's capacity. Jon M. Huntsman Hall's 2016 opening broke the campus bottleneck, with classrooms and other spaces dedicated to business school participants. "But we still needed space for our centers and experiential learning programs," Caliendo said, of the importance of collaborative spaces and differentiated experience for the five programs (see page XX) that would call the Gardner Building home. The design intent for this final piece wasn't a re-creation of Huntsman Hall, Caliendo said of the initial message to MHTN Architects, "But it does need to rhyme with Huntsman Hall." Working within a Busy Environment The first order of business was siting the building just east of the other two business school structures. Stan Burke, Project Manager for Jacobsen Construction, said the Gardner Building was part of a trio of projects that included Ridge Point Hall and a parking garage—three Jacobsen-led projects that utilized the same construction corridor as construction commenced from "An active campus is difficult enough," said Burke of the challenges of simultaneous construction, which required constant coordination amongst the three teams, made a tad easier as they shared a job trailer. "We had to stay cognizant of the school's activities and coordinate with them so that everyone was aware of what we were doing." Coordination went from important to critical, with the three teams meeting daily to discuss coordination and scheduling material and equipment deliveries in 15-minute intervals as the respective construction teams worked on each of the three structures.

Warren and Jennie Lloyd (above) have built Salt Lake-based Lloyd Architects into a well-rounded, versatile firm capable of excelling in both the commercial and custom residential markets, as evidenced by projects such as Snuck Farm in Pleasant Grove (main photo) and this cozy private Powder Mountain based cabin in Eden (below ).

The last five years have been a whirlwind for the Larry H. Miller Company (LHM), with the organization selling the majority of its beloved Utah Jazz franchise in October 2020 for a reported $1.66 billion, followed by the sale of its auto dealership empire of more than 70 properties for a reported $3.2 billion a year later. The influx of nearly $5 billion was parlayed into several jaw-dropping real estate and other corporate purchases, including: —1,300 undeveloped acres within the massive 4,100-acre Daybreak development in South Jordan in April 2021. —Advanced Health Care Corp. in January 2021, a transitional health care provider with operations in eight states (primarily in the west) and 3,500 employees. —The purchase of the majority stake in Swig, a leader in the flavored soda craze, in May 2023. — Partnering with Utah Trust Lands Administration to develop 1,200 acres in Saratoga Springs. — The acquisition of over 1,000 acres near Park City and Hideout will include multi-family units, housing, restaurants, and retail. —100+ acre mixed-use development in an area along North Temple being dubbed “The Power District”; the future home of not only Rocky Mountain Power’s new corporate campus but potentially a ballpark for a future Major League Baseball expansion team. —A reported $600 million acquisition of controlling interest in MLS team Real Salt Lake and NWSL team Utah Royals, along with associated infrastructure, including America First Field and Zions Bank Training Center. —The development of Downtown Daybreak, a 200-acre parcel that this year saw its 30-acre Phase I debut with the completion of the Salt Lake Bees' new 8,000 capacity stadium—dubbed The Ballpark at America First Square—in April, followed by a new Megaplex cinema entertainment center in July with luxury theatres, bowling, games and a scratch-made kitchen in addition to an open air plaza. A seven-story, 190-unit multi-family development is currently under construction and rising along the right field bleachers, with views that will look down into the ballpark upon completion next year. And LHM is just getting started, said Brad Holmes, President of Larry H. Miller Real Estate since 2018, calling Downtown Daybreak a "new urban center that is central to where the majority of growth is occurring" and combines a "full spectrum of business and year-round entertainment, culture and connectivity, as well as a wide range of housing options." When LHM executives first conceived of a new home for the Salt Lake Bees, Holmes said they went on a "ballpark tour" of MLB and minor league stadiums, and "really fell in love with a ballpark" in Durham, North Carolina—home of the Durham Bulls—which had buildings that framed in the stadium. So, The Ballpark at America First Square has the multi-family project underway in right field, with a proposed hotel slated to begin next year in left field. "In another two seasons, you'll have this urban setting for the ballpark that frames the mountain views. [The design is] really intentional, and I think it will bring a finished edge to Downtown Daybreak," said Holmes. "It was a process trying to figure out the best location, site plan, traffic, but it's in a great spot. The goal for us was to make it feel like it fit in with the community, almost like having a baseball stadium inside of a park, with an open corridor that connects to a plaza." Holmes said the seemingly small 8,000-capacity stadium (about half the capacity of the Bees former home at Smith’s Ballpark) aligns with national trends. "It's better to play in front of a sold-out crowd than in a half-empty stadium. Some new MLB stadiums are at 30,000 [capacity]. The trend is smaller, more intimate venues with closer views of the field."

Much has changed about Hogan & Associates Construction since the company's inception 80 years ago. The name may be the most obvious example, the size of the company may be another giveaway, and the difference in markets served might require a double take if the founders could see the company today. But what hasn't changed is the firm's desire to build communities. It has regularly built important, community-focused projects with a similar purpose since the company came to life in 1945.

Imagine this: A company has just begun a meeting with the intent of moving forward with a major investment. One party knows something that will help minimize the investment's risk. Should that party tell everyone, it will save money, time, and everyone involved from future headaches. So when should that party spill the beans? At the beginning of the meeting At the end of the meeting At the right time during the meeting Never Bradley Crocker, Director of Preconstruction for Mollerup Glass, has seen how answering this question correctly—and choosing “A”—brings about successful and profitable investment in commercial construction. “I think that [project teams] need to bring in subcontractors early to help guide budgets in general,” said Crocker, detailing how every trade can bring a similar level of expertise to architects and owners by being involved from the beginning of the “meeting”, while the project is in design. Why? “We can vet cost versus performance and find the best value for the performance, which is essential as meeting or beating the budgets gets the project to construction on time,” said Ben Hiatt, Chief Estimator for Steel Encounters. After all, he said, “Nothing moves if budgets are not met.” Design-assist is a positive step forward, where subcontractors assist in matching design intent with a deep understanding of building envelopes to ensure glazing, roofing, walls, and fenestrations perform at their highest level. Glenn Rainey, Salt Lake City Branch Manager, and Larry Luque, Senior Estimator and Business Developer for Flynn Companies, each said efforts in design-assist fulfill what owners and architects want: buildings that meet the design intent and perform at their highest level for as long as possible. It’s not just architects who benefit from that early involvement. “More GCs realize they need us right up front,” said Luque. With teams whose combined experience totals thousands of hours, building envelope contractors stay up to date on changing codes, materials, and specifications, which is highly beneficial to the project. Their close involvement with vendors can help ensure a variety of solutions that meet each job’s needs and help optimize building envelope performance. Consultant Involvement Other parties are lending their expertise. Brandt Strong said building envelope quality has increased with the arrival of more building envelope consultants in Utah and a greater dedication to the building envelope in general. “We had a time where we could say ‘This is a Vegas project, and we have to have the belt and suspenders,’” said Strong, Director of Operations for Mollerup Glass. On Utah projects, the building envelope used to be an afterthought. But it’s changed for the better over the years. “The Utah teams are as sophisticated as anywhere else.” While the markups on shop drawings can draw some ire, both mentioned how working with consultants has led to better, more efficient projects, potentially reducing the need for future repairs by inspecting every material and transition on the building envelope. Said Crocker, “We cannot discredit the envelope consultants’ role in making us, and the industry as a whole, perform at a higher level.” Hiatt credited each party overseeing the building envelope scope for learning and adapting to create a better building environment, specifically in understanding seismic drift and its relationship to glazing, as well as thermal performance and continuity. Improvements to air-barrier coordination and tie-ins to stop water and air leaks are helping buildings operate at peak efficiency. “The architects, general contractors, consultants, and trades have improved their knowledge over the years,” said Hiatt. “Design and execution of façades are better coordinated and executed.”

By Bradley Fullmer It's been a whirlwind 18 months for Adam Del Toro and Nick Pexton, who co-founded Fountain Green-based Reliance Engineering Services in May 2024, a company specializing in full-service telecommunications engineering, including design, project management, permitting, and funding and grant applications. Two years ago, Del Toro was more than a decade into his career as a Research & Development Supervisor for natural gas giant Dominion Energy, while Pexton was working for Nephi-based Rocky Mountain West Telcom (RMWT) as a Sr. Director of Business Development, with just over four years at the company. The two had met a couple of years earlier while collaborating on a potential fiber optic network project in Mona that never happened. Neither was particularly content with their respective positions, so when Del Toro got a random call from Pexton in March 2024, the timing could not have been better. "I was planning on leaving the natural gas industry and start my own firm [...] Nick happened to call the day I was putting in my two weeks [at Dominion],” said Del Toro, 39. "It definitely felt like Providence was helping us." "Somebody was looking after us, because the timing was unbelievable," added Pexton, 35. "It's crazy how things lined up." Del Toro is a native of St. George and earned a Bachelor of Mechanical Engineering from Utah State University in 2011. After 2.5 years as a USU Graduate Research Assistant, he joined Dominion Energy in January 2013, where he designed major natural gas systems and structures. Del Toro also earned a Master of Clinical Mental Health Counseling from the University of the Cumberlands (Williamsburg, Kentucky) in 2023, and moonlights as a counselor at The Center for Hope in Springville, where he helps clients address life challenges both personally and professionally. Pexton is a native of Nephi and studied at Utah Valley University from 2008 to 2010, and earned the Certified Telecommunications Network Specialist designation from Teracom Training Institute (2013-2014). Pexton joined Nephi-based Mid-State Consultants, a telecommunications engineering firm, in March 2011 and spent more than nine years there. He joined RMWT in June 2020, gaining experience in project management and operations. After that fortuitous phone call from Pexton to Del Toro, the pair met four times from March to May to "make sure we were aligned on what the company would look like," Pexton said. "It was a pretty quick process," added Del Toro. "We got talking about goals, how to build a general company vision. I trusted Nick's background and experience, and his character, as well. It was a big risk, but I'm a sink-or-swim guy. If those are my options, I'm going to swim!" Since teaming up, the pair have been aggressive regarding company growth, having exploded from just the two of them to 30 employees, with revenues expected to more than quintuple from $560,000 in 2024 to nearly $3 million by the end of this year. Both expect the telecommunication market to be a fruitful, busy market given the need for fiber optics to rural America, in addition to the "Internet for All" initiative in May 2022 that was part of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration's (NTIA) implementation of the infrastructure law that allocated $65 billion to improve high-speed Internet access. Utah, specifically, received $330 million, with the goal of reaching some 40,000 unserved homes and businesses. The firm's location in Sanpete County puts them in the center of the state geographically, and they're committed to working with communities of all sizes to improve their internet capacity. In addition to Utah, Reliance is working in Michigan and Oklahoma, and Del Toro and Pexton expect to land significant future work throughout the Midwest. They want to grow intentionally while ensuring a diversity of revenue streams. "We set some early goals, and we've been able to do really well—we're on track to beat our goals," said Del Toro, crediting the many employees who have joined the firm. "Those individuals took great risks coming on board. We anticipate we'll be even larger next year with the work coming down the pipeline." "Our outlook has been wise," said Pexton. "We've taken into consideration diversification into other sectors—that's a key element. Adam has experience in the natural gas industry, and we want to further our diversification and get into the power side of the industry." Major clients include the federal government (USDA), utility companies, and municipalities, with a focus on rural communities. "We love Sanpete County," said Del Toro. "We value helping the communities we live and work in and providing services that help build up the community and hopefully help the residents." "We depend on repeat work from 18 major clients, and continuously getting work from them," said Pexton. "The minute we stop doing a good job, they can go someplace else. As long as we do a good job, we'll keep getting work." The pair expect Reliance to maintain its explosive growth, perhaps even doubling its employee total in another 12 months. "Next year's [revenue] goal is $4.8 million," said Pexton. "We have confidence in what our workload will be like. We are scaling quite dramatically and want to grow at a healthy pace, where we're not stringing ourselves out too thin. We're in a good position right now."